For years, financial planners have advised clients to gradually adjust the mix of stocks and bonds in their retirement accounts from stock-heavy and bond-light when they're young, to stock-light and bond-heavy as they approach retirement. The underlying rationale is that stock returns and risks are higher relative to bonds, and therefore more appropriate for young investors who have many years to build wealth and recover from stock market downturns. Older investors need to be more conservative (fewer stocks/more bonds) as they don’t have as many years to recover from market set-backs.

The conventional rule-of-thumb guiding the appropriate stock/bond mix is based on the investor’s age, and says an individual’s portion of stock holdings should be 100 minus their age, with the remainder going into bonds. Example – a 70 year old should have 30% of their holdings in stocks and 70% in bonds.

As people are living longer and bond yields are historically low, the 100 in the 100-minus-the-age formula has been updated to 110 or even 120.

Side note: Financial planners will typically recommend that an investor’s stock holdings be in a low-fee, index mutual fund that mimics the broader market (ex: an S&P 500 index fund) and bond holdings in US Treasury debt (notes and bonds) and investment grade corporate bonds.

Side note part deux: Investment grade is determined by the bond rating agencies like S&P, Moody’s, or Fitch. You might opt to outsource here and invest in a bond fund to diversify and let someone else worry about which bonds are investment grade and which aren’t. Frankly, the Unrepentant Capitalist has never been able to keep the various bond scoring systems straight. Is a AAA- rating better than Aaa? Aa?

When you buy a bond, whether you realize it or not, you’re placing a bet on the future direction of interest rates.

Finance 101 teaches us that bond prices and bond yields move in opposite directions. As rates increase, bond prices fall, and vice versa.

A simple example – if I buy a 30-year bond issued with a 5% interest rate, and 1 year later rates have dropped, and new 30-year bonds are being issued with a 4% rate, my piece of paper with its 5% interest rate is more valuable to investors relative to the current 4%. Interest rates have fallen and my bond is worth more.

Conversely, if 1 year from now, long rates have climbed to 6%, my 5% bond will be worth less. You only lose money if you sell, but how many retirees will hold their bonds the full 30 years?

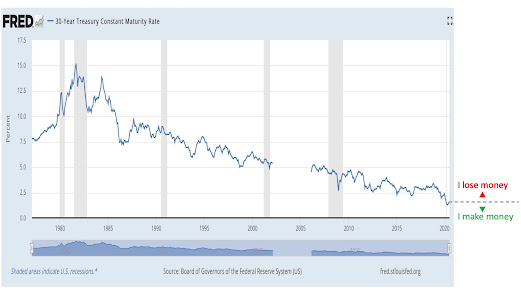

The chart below is from the St Louis Fed and shows interest rates on the 30-year bond going back to 1977. (chart

If you’re putting money in bonds today with interest rates near historical lows, you’re betting that curve continues to go down. Anything’s possible, but there’s a lot more history above the curve than below it. It seems more likely that rates move higher/back towards the mean* with the economy on the mend after the COVID shutdown.

The Unrepentant Capitalist is not a financial advisor, and he’s not a bond buyer here.

In a future posting, the Unrepentant Capitalist will discuss a stock/bond mix rule based on when the investor will need to tap into their retirement funds. There's a risk to being in the market, and equally important, there's a risk to being out of the market.

In a future posting, the Unrepentant Capitalist will discuss a stock/bond mix rule based on when the investor will need to tap into their retirement funds. There's a risk to being in the market, and equally important, there's a risk to being out of the market.

*The long-term average interest rate on the US 30-year Bond is 6+%.

No comments:

Post a Comment